That ingenuity took the form of a digital copy stand, which I still use today. I thought I would be able to solve the problem with a little ingenuity. Any change or movement at that point would have made a visible difference in the film, so I stayed with the status quo. By the time I could see the extent of the problem, I was five months into a 15-month project. Why didn’t I fix the problem? It took five months to accumulate enough processed film to make a test of the telecine conversion (a pricey $300 per hour). The film exposed by the second camera worked quite well. The inconsistent feed was beyond the range of correction possible on the telecine machine. Converting the film frames to video requires a device called a telecine machine, and these devices presume frame-accuracy. Sometimes one camera skipped a sprocket while advancing the film, which was fatal to the film from that camera. The relationship between the image and the sprocket holes varied considerably during the project. Nikon F3s are not frame-accurate because they don’t have a pin-register mechanism. It all would have worked fine except for mechanical problems with one of the cameras. Over 15 months, the cameras made a total of about 11,000 frames.

I reloaded the film cartridges and mailed them back to the hangar for the next two weeks. The camera’s view of Hangar 63, in which GlobalFlyer was taking shape.Įvery two weeks, a technician put in fresh film and mailed the exposed film cartridges to a processing lab in Burbank, which sent me the processed film.

We attached two Nikon F3 35mm film cameras on the hangar walls and began a time-lapse project that lasted well over a year (Figure 2).įigure 3. My project partner Jim Sugar and I had been given exclusive photo access to that plane, and we were there when the first spar of carbon-fiber epoxy was removed from the curing oven. (The plane flew non-stop around the world in March 2005, setting numerous world records). Years passed before the next time-lapse opportunity: to document the construction of Global Flyer, an airplane designed and built by the legendary aircraft designer Burt Rutan at Scaled Composites in Mojave, California. This turned out to be an “educational experience” - that is, a flop. Double-or triple-speed would have been fine. I had chosen too long a period between frames. The most significant was that it ran way too quickly the balloons were inflated and disappeared out the top of the frame in less than a second. My film, after processing, suffered from several problems. But the wind picked up, making balloon launches dangerous, so only two pilots chose to fly. I started the camera before sunrise on the appointed day, then joined the balloonists. That calculation was based on how many frames there were on 400 feet of film (16,000 frames, running time about 11 minutes) divided by the number of hours I estimated the event to last (about three). I set the camera on a tripod on the hill above the event, loaded it with 400 feet of 16mm motion picture film, and set the timer to take one frame every few minutes. My plan was to photograph the launch of a dozen hot-air balloons. This old-school time-lapse camera is a Mitchell 16mm animation camera with an electronic intervalometer. I rented a 16mm time-lapse camera with a double pin-register mechanism and an electronic timer to expose the frame and advance the film (Figure 1).įigure 1. I first attempted a time-lapse film more than 20 years ago.

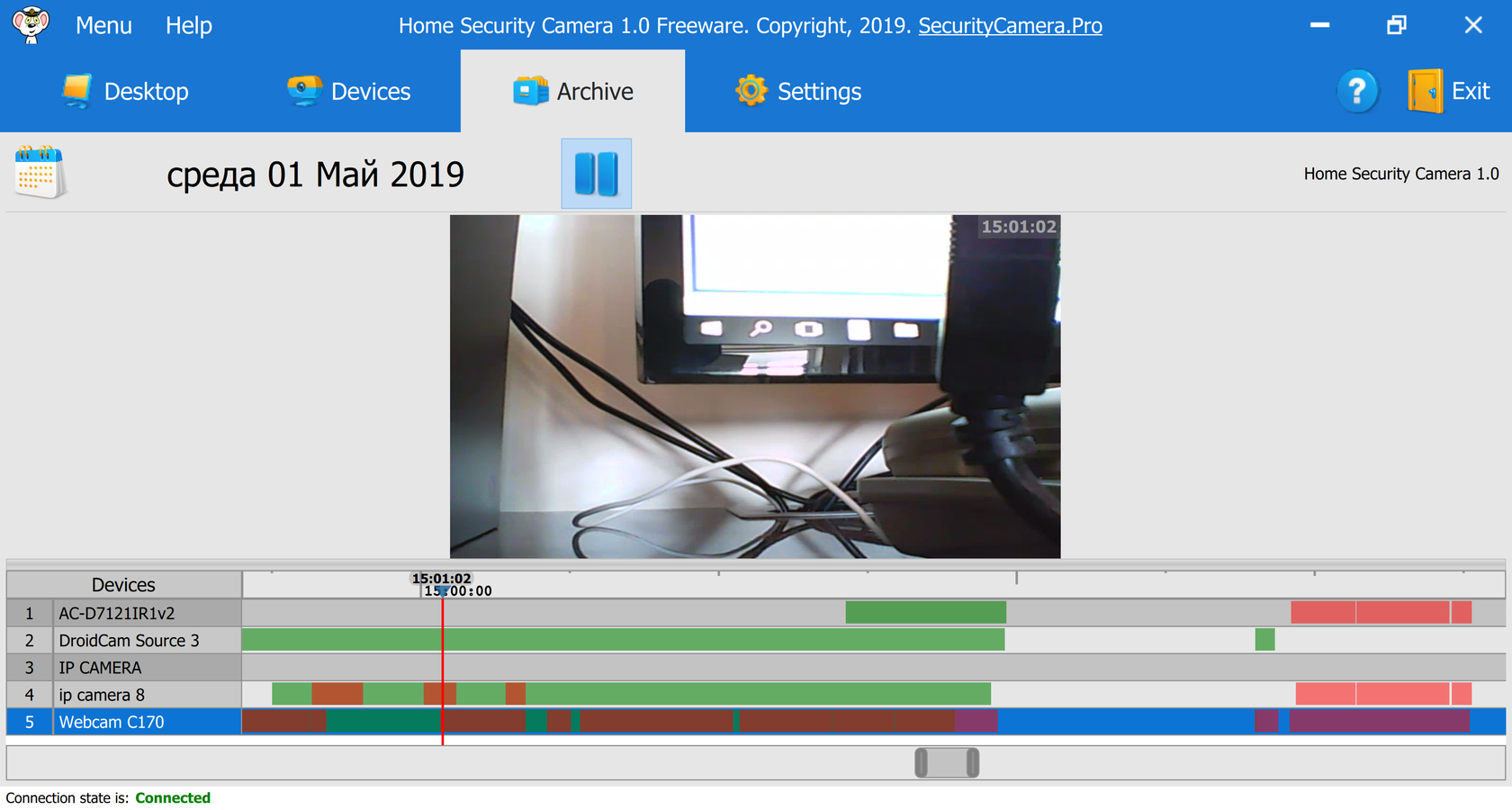

FREE TIME LAPSE SOFTWARE FOR IP CAMERA SERIES

The traditional time-lapse photography materials include motion picture film cameras with one or two pin-register mechanisms to keep the picture accurate relative to the sprocket holes and an intervalometer, an electronic timer that exposes a frame or series of frames at a set interval. But cobble together a cheap digital camera, a $129 timer, and a motorcycle battery, and you’ve got the basics of a system that can go far beyond clichés.

Hackneyed examples include flowers unfolding in the sun and clouds passing across scenic horizons. With time-lapse photography, it’s possible to compress time into short periods, making days or weeks pass by in seconds. Time-lapse photography is a variation on this. It wasn’t long after the invention of motion pictures that camera operators and directors intentionally ran the camera faster or slower than normal to create special effects. Undercranking (running the camera slowly) and overcranking (running the camera faster than the projector) caused a film to appear faster or slower than reality. Matching the projector’s speed with the speed of the camera made the motion lifelike. Movies were born when Auguste and Louis Lumiere (and ultimately Thomas Edison) projected a series of still photos in rapid succession, causing the viewer to perceive motion where there was none.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)